Digital Exclusive: Building resilient safety cultures: A competence-based approach for high-hazard industries

H. DUTTA and F. AKHTER, Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

Major incidents in the high-hazard hydrocarbon processing industry (HPI) continue to occur with alarming regularity, often revealing familiar patterns of failure. While technical and engineering safeguards are critical, investigation reports frequently point to deeper, more systemic issues rooted in organizational culture, leadership and competence.

This article argues that a paradigm shift is needed, moving beyond a compliance-based mindset to one focused on building profound and verifiable competence at every level of an organization. It deconstructs the essential pillars of a robust process safety culture, examines the indispensable role of leadership in championing this culture and provides a comprehensive framework for competence building. Using a 2020 styrene gas leak in a polymer factory as a case study, this article explores the anatomy of a process safety failure and identifies 10 critical gaps commonly observed in the industry. It delves into the human paradoxes that often undermine safety efforts and explores how emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) can be leveraged to create more predictive, responsive and resilient safety systems. The central thesis is that sustainable process safety performance is not merely the absence of incidents but the presence of a deeply embedded, competence-driven culture of safety.

What is process safety? The HPI is the backbone of the modern global economy, yet it operates at the frontier of immense risk. The handling of volatile, flammable and toxic materials at high pressures and temperatures creates a constant potential for catastrophic events that can result in significant loss of life, environmental devastation and financial ruin. Despite decades of learning, the implementation of sophisticated process safety management (PSM) systems, and a stated commitment to safety, major accidents persist. The question that the industry must continually ask itself is: Why do major incidents repeat?

The answer, as this article will demonstrate, is often found not in the engineering diagrams or the process flow charts, but in the complex interplay of human factors, organizational priorities and workplace culture. Time and again, incident analyses reveal that the root causes are less about faulty equipment and more about a faulty safety culture, a culture that allows for the normalization of deviance, discourages the reporting of bad news, and permits a gap to grow between written procedures and work-as-done.

Process safety is not a static set of rules; it is a dynamic capability that must be continually nurtured and developed. It requires an organization to be in a state of chronic unease, constantly vigilant for weak signals of emerging risks. This vigilance is built on a foundation of competence the demonstrable ability of individuals and the organization to manage process safety risks effectively.

This article provides a roadmap for building that competence. It entails the core tenets of process safety and its foundational pillars. It then analyses a significant industrial accident to illustrate how failures in these pillars, driven by cultural deficiencies, can lead to catastrophic Incident. Subsequently, it enumerates the essential elements of a positive safety culture, the critical role of leadership, and a ten-point framework for building sustainable competence. Finally, the pervasive gaps and human paradoxes that hinder progress and look toward the future role of technology in strengthening our defences are discussed.

The foundations of process safety. Process safety is not an adjunct to operations, maintenance or design, it is an integral part of them. It is fundamentally different from personal safety (e.g., slips, trips, falls). While personal safety is concerned with preventing individual injuries, process safety is focused on preventing low-frequency, high-consequence events involving the uncontrolled release of energy or hazardous materials. Understanding and managing these risks requires a formidable combination of in-depth domain knowledge, sound technical skills, acute analytical capabilities and a sophisticated understanding of human and organizational processes.

A holistic approach to process safety can be modelled on four key pillars of integrity that must work in concert to ensure the safety and reliability of an asset:

- Design integrity: This is the first line of defense. It ensures that facilities are designed and constructed based on sound engineering principles, incorporating inherently safer design concepts where possible. This includes correct material selection following the relevant standards, proper equipment specifications, robust control and shutdown systems, and layout considerations that minimize risk.

- Operational integrity: This pillar concerns the safe and effective operation of the facility within its design limits. It involves having clear, accurate operating procedures, a well-defined safe operating envelope and robust management-of-change (MoC) processes to evaluate any deviations from the original design or operating intent, including handling emergencies and trouble shootings.

- Maintenance integrity: Assets must be maintained in a fit-for-service condition. This involves proactive inspection, testing and preventive maintenance programs for critical equipment. It ensures that equipment failures are prevented and that any discovered deficiencies are corrected promptly. Maintenance practices like risk-based inspection and reliability centric maintenance enables industry to help prevent failures.

- Asset integrity: This is the overarching outcome of the other three pillars. Human resources are the key and are central to managing the processes and practices. Are the human assets in the organization motivated and well trained? Are they engaged? Are they part of the decision-making process? Is the quality of training and re-training considered a priority, or it is just a routine?

When any one of these pillars weakens, the entire structure is compromised, creating the conditions for a major accident.

A CASE STUDY IN FAILURE: A STYRENE GAS LEAK

On May 7, 2020, a catastrophic gas leak occurred at a polymer plant in southern India, releasing a cloud of toxic styrene vapor into the surrounding community. The incident resulted in 12 fatalities and the hospitalization of over 1,000 people, affecting residents across five nearby villages. The event serves as a tragic and powerful illustration of how latent failures across the pillars of process safety, rooted in a weak organizational culture, can culminate in disaster.

FIG. 1. A toxic styrene leak at a polymer plant in southern India released a cloud of toxic styrene vapor into the surrounding community, killing 12 and hospitalizing over 1,000.

The incident. The leak originated from a large-scale styrene storage tank. The facility had been shut down for over 40 days due to a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, and personnel were in the process of preparing for its reopening. Approximately 1,800 metric tons of styrene monomer were being stored in a 2,400-t capacity tank. During the shutdown period, a lack of oversight and control allowed the conditions for a runaway chemical reaction to develop.

Technical failures and contributing factors. Styrene is a reactive chemical that can undergo hazardous polymerization, an exothermic reaction that generates significant heat. To prevent this, it must be stored at temperatures below 20°C and treated with an inhibitor chemical (such as tertiary butylcatechol or TBC). The investigation into the leak revealed a cascade of failures:

- Poor design integrity: The storage tank itself was of a poor design, originally intended for storing molasses, not a hazardous chemical like styrene. This fundamental flaw created inherent risks from the outset.

- Failure of maintenance and operational integrity: The refrigeration and cooling system designed to maintain the low storage temperature was inadequate. Critically, an adequate quantity of TBC inhibitor was not added to the tank to prevent the onset of the polymerization reaction.

- Inadequate monitoring: The temperature monitoring system was insufficient. As the polymerization reaction began at the top of the tank, the heat generated caused the temperature to rise uncontrollably. This rise went undetected, leading to a runaway reaction where the styrene began to boil, generating a massive volume of vapor that overwhelmed the tank's vents and was released into the atmosphere.

- Lack of emergency preparedness: The facility was ill-prepared for such an emergency, with a clear lack of robust emergency response procedures to mitigate the consequences of a release.

The cultural roots of catastrophe. Why did these errors occur? Was it simply a series of isolated technical mistakes? The evidence suggests a deeper problem. The litany of failures points not just to individual lapses but to a systemic breakdown in the organization's safety culture. Besides, it is well known that five times more process safety incidents take place during plant startup. The incident raises critical questions about the organization's training, motivation and reporting systems. It highlights a potential gap between stated policies and actual practice, a classic symptom of a weak safety culture where production or cost-saving imperatives silently override safety protocols. Such incidents underscore a fundamental principle: making a mistake is human, but allowing the conditions for the same types of mistakes to persist is a sign of a failed organizational learning process. The ultimate purpose of any investigation or disciplinary action must be to ensure that the occurrence never happens again.

Anatomy of a robust safety culture. A resilient safety culture is the "social glue" that binds a PSM system together. It is the shared values, beliefs and behaviors that determine how safety is managed in practice. It is what people do when no one is watching. A positive and effective safety culture is not built by chance; it is cultivated through deliberate action and is characterized by six essential attributes:

- An informed culture: Everyone in the organization—from the boardroom to the frontline—understands the hazards and risks inherent in the operations. There is a clear and shared understanding of the company's commitment to safety, its core values and its goals.

- A reporting culture: People are not only willing but encouraged to report errors, near-misses and safety concerns without fear of blame or retribution. The organization views these reports as invaluable opportunities for learning and proactive improvement.

- A learning culture: The organization actively seeks to learn from its experiences and those of others. Incident investigations go beyond immediate causes to find systemic root causes. Training is an ongoing process, and the organization is constantly striving to move from a reactive (fix-it-when-it-breaks) mode to a proactive and predictive state.

- A just culture: A "just culture" fosters an atmosphere of trust. While it does not tolerate willful negligence or malicious acts, it ensures that individuals are not punished for honest mistakes. It draws a clear line between acceptable and unacceptable behavior, encouraging people to admit to errors so that the system's weaknesses can be identified and fixed.

- A flexible culture: The organization is not rigid or complacent. It is willing to adapt and make necessary changes to improve safety. It empowers people at all levels to make decisions, particularly in situations where stopping a job is the safest course of action.

- A trusting culture: There is a fundamental belief that everyone is working towards the common goal of safety. This creates a synergistic environment where problems are solved collaboratively, breaking down the "us vs. them" mentality that can exist between management, staff and contractors.

The catalyst for change: Proactive safety leadership. Systems, procedures and cultural aspirations are meaningless without the visible, unwavering commitment of leadership. Leaders at all levels are the ultimate arbiters of what truly matters in an organization. Their actions or inactions send the most powerful signals about whether safety is a core value or just a slogan. Building a strong safety culture requires a specific and demanding brand of leadership:

- Leaders who cultivate a chronic sense of unease: High-reliability organizations lack complacency. They understand that a good safety record today is no guarantee of safety tomorrow. Leaders must instill this sense of unease, constantly challenging assumptions and looking for the next potential failure.

- Leaders who welcome bad news: They actively work to remove the organizational barriers that prevent bad news from traveling upwards. They understand that an unreported near miss is a missed opportunity for learning and that a culture of fear is a precursor to disaster.

- Leaders who are visibly present: True commitment is demonstrated in the field, not just in the boardroom. Leaders must be willing to conduct safety tours, participate in audits and engage in meaningful conversations with the workforce to understand the real-world safety issues they face.

- Leaders who prioritize safety over profitability: When conflicts arise between short-term budget constraints or production targets and long-term process safety assurance, effective leaders consistently choose safety. They ensure that incentive schemes do not inadvertently encourage risk-taking by rewarding production at the expense of safety.

- Leaders who institutionalize safety: They move the organization's safety approach from being dependent on a few key individuals to being embedded in the institution's systems, processes and culture. They ensure that process safety has a permanent and prominent place on the agenda for all board meetings.

Leadership is the engine of continuous improvement. By demonstrating these behaviors, leaders assure the organization to make safety their core value.

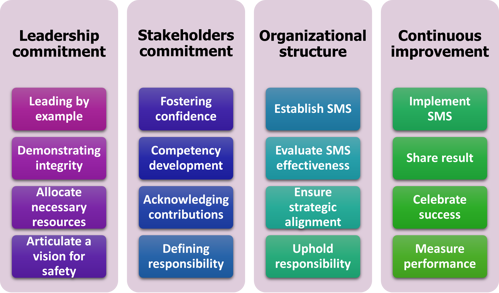

A blueprint for action: 10 pillars of competence building. Building a robust process safety culture is an active process of building competence at both the individual and organizational levels (FIG. 2).

FIG. 2. A blueprint for building a robust safety culture.

It is a comprehensive endeavor that requires a multi-faceted approach focused on developing and sustaining the knowledge, skills and systems needed to manage risk effectively. The following 10 pillars provide a framework for this critical work:

- Training and education: Competence begins with knowledge. Organizations must invest in comprehensive, role-specific training programs that go beyond mere compliance. This training should cover safety procedures, emergency response, hazard analysis techniques and the "why" behind the rules, ensuring employees have the skills to identify, assess and manage risks in both routine and non-routine situations.

- Psychological safety: This is the bedrock of a reporting and learning culture. It is the creation of a safe and inclusive environment where every employee feels empowered to report concerns, share ideas for improvement and admit to near misses without any fear of coercion or punishment. This requires an absolute commitment to non-punitive reporting systems.

- Leadership commitment: As detailed previously, leadership is not a passive endorsement but an active, visible and consistent engagement in all aspects of process safety. Leaders must "walk the talk" by prioritizing safety resources, holding everyone (including themselves) accountable and actively promoting safe behaviors.

- Continuous improvement: Process safety is a journey, not a destination. Organizations need robust systems for learning and adaptation. This includes processes for thoroughly investigating incidents, tracking corrective actions to completion and regularly auditing management systems to identify areas for improvement.

- Organizational competency: This involves weaving process safety principles into the fabric of the entire organization. It means applying a safety lens to all operational phases, from initial design and engineering through procurement, construction, maintenance and eventual decommissioning.

- Communication and collaboration: Effective, multi-directional communication is vital. Clear channels must be established to share information, lessons learned from incidents and best practices across all departments, sites and hierarchical levels. This also includes collaboration with external stakeholders.

- Learning from incidents: A mature organization does not waste the learning opportunity presented by an incident or near-miss. It establishes a robust investigation process that digs deep to uncover not just the immediate causes, but the underlying systemic root causes related to its management systems and culture.

- External engagement: No organization operates in a vacuum. It is crucial to collaborate with industry associations, regulatory agencies and local communities to stay informed about emerging trends, regulations and best practices. This external focus helps prevent organizational insularity and promotes shared learning.

- Leading and lagging indicators: To effectively manage performance, one must measure what matters. This means moving beyond a sole reliance on reactive, lagging indicators (like incident rates) and developing a balanced scorecard of proactive, leading indicators. Leading indicators (e.g., status of safety-critical maintenance, number of near-misses reported, audit findings closed on time) provide insight into the health of safety barriers before an incident occurs.

- Reward and recognition: Positive behaviors should be reinforced. Organizations should design recognition and reward programs that celebrate proactive safety contributions, such as high-quality hazard identification, active participation in safety committees or courageous use of stop work authority. This helps to make safety a valued and celebrated part of the culture.

By systematically building these 10 pillars, an organization can create a self-reinforcing system that drives improved safety performance and reduces the risk of major accidents.

Confronting reality: Observed gaps in industry process safety culture. Despite the widespread adoption of PSM frameworks, a significant gap often exists between policy and practice. The following are 10 critical areas where deficiencies are commonly observed in the industry, particularly in regions where safety culture is still maturing:

- Training and education gaps: Training is often treated as a compliance checkbox rather than a true competence-building activity. There is a frequent disconnect between classroom training and verified on-the-ground competency. This gap is especially pronounced for contract workers, who are often involved in high-risk tasks but receive the least amount of training and are frequent casualties in accidents.

- Psychological safety gaps: A culture of fear and blame often suppresses the reporting of near misses, which are vital for proactive learning. In many cultural contexts, hierarchical norms make it difficult for junior employees to challenge superiors or speak up about hazards, effectively silencing a crucial source of safety intelligence.

- Leadership commitment gaps: A credibility gap emerges when leadership's words about safety are not matched by their actions. Decisions to cut costs on maintenance, delay critical upgrades or pushing production despite known risks directly undermine any safety-first messaging. This commitment often dilutes as it moves down the hierarchy, failing to reach the frontline where it is needed most.

- Continuous improvement gaps: Many organizations remain stuck in a reactive mode, only making significant improvements after a major incident has occurred. There is a tendency towards a minimalistic compliance mindset rather than viewing PSM as a system for continuous risk reduction. This leads to the normalization of deviance, where small leaks, bypassed alarms and procedural shortcuts become accepted daily practice.

- Organizational competency gaps: In some regions, the lack of a single, comprehensive and robustly enforced PSM regulation creates an inconsistent safety landscape. Aging infrastructure presents a significant challenge for implementing modern safety standards. Furthermore, the increasing outsourcing of core functions like maintenance can dilute in-house competency and diffuse accountability for safety.

- Communication and collaboration gaps: Poor shift handover communication remains a classic root cause of major accidents. Information often exists in fragmented data silos, hindering effective decision-making and emergency response. Communication is typically top-down, with few effective channels for workers to voice concerns upwards.

- Learning from incidents gaps: Incident investigations are often superficial, stopping at "human error instead of identifying the organizational and systemic failures that set the individual up for failure. This leads to a tragic cycle of recurring incidents with identical root causes, demonstrating a clear failure to learn from experience.

- External engagement gaps: The relationship with regulators can be adversarial or merely compliance-driven, missing the opportunity for a collaborative partnership for improvement. Similarly, community engagement is often reactive, happening only after an incident, rather than being a proactive effort to build trust.

- Leading and lagging indicators gaps: There is a pervasive over-reliance on lagging indicators like the lost-time injury rate as the primary measure of safety. This focus on past failures provides little predictive insight and can create a dangerous false sense of security when rates are low, masking significant underlying process safety risks.

- Reward and recognition gaps: When incentive programs do exist, they are often poorly designed. Linking bonuses to lagging indicators like zero accidents can have the perverse effect of discouraging the reporting of incidents and near-misses. There is a need to shift towards behavior-based reward programs that incentivize proactive safety actions.

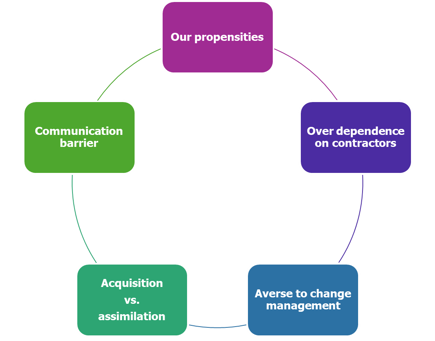

The human dimension. Navigating psychological paradoxes in safety. Even with the best systems in place, human behavior remains a critical variable. Organizations must understand and address several deep-rooted human propensities, or paradoxes, that can undermine safety:

- The learning paradox: We give great importance to lessons learned but repeatedly fail to truly learn from them, as evidenced by the recurrence of similar incidents. There is often an attitude of being too knowledgeable that prevents us from challenging our own assumptions and learning processes.

- The technology paradox: We are quick to acquire state-of-the-art technology but often fail to properly assimilate it. This means not investing enough in the training, education and coaching required for people to understand, operate and maintain the new technology safely.

- The outsourcing paradox: In a drive for efficiency, many core tasks are outsourced to contractors. However, this often leads to an over-dependence on these contractors without adequate supervision or verification of their safety processes and the competency of their workers.

- The change management Paradox: While MoC is a core tenet of PSM, there is a strong human aversion to its rigorous application. This manifests as the bypassing of protective layers, the failure to conduct proper risk assessments for new facilities or modifications, and a general disregard for maintaining accurate documentation.

- The communication paradox: In many hierarchical cultures, communication is not a dialogue but a monologue. We instruct rather than engage. There is a reluctance to ask questions, allow dissenting views, or facilitate a collaborative problem-solving process, which stifles the flow of critical safety information.

FIG. 3. Even with the best systems in place, human behavior remains a critical variable.

The next frontier: Enhancing process safety with AI. As we look to the future, technology offers powerful new tools to augment our competence-building efforts. AI can significantly enhance process safety culture by providing data-driven insights, predictive analytics and real-time monitoring on a scale previously unimaginable. Key applications include:

- Predictive analytics and hazard identification: AI algorithms can analyze vast datasets from sensors, maintenance records and operational logs to identify subtle patterns and correlations that precede failures. This allows for a shift from preventive to predictive maintenance, and a more proactive identification of emerging hazards.

- Real-time monitoring and alerting: AI-powered systems can monitor complex operations in real-time, detecting deviations from safe operating envelopes far quicker than human operators. They can provide early warnings and alerts, enabling faster intervention before a situation escalates.

- Automation and optimization: AI can automate routine, high-risk tasks, reducing human exposure to hazards. It can also optimize complex processes, ensuring they run more efficiently and consistently within safe limits.

- Personalized safety training: AI can be used to develop adaptive training programs that are tailored to the individual needs and knowledge gaps of each employee, making training more effective and engaging.

- Enhanced decision-making: By processing massive amounts of information and running complex simulations, AI can provide leaders and engineers with richer, data-driven insights to support better risk-based decision-making.

While AI is a powerful tool, it is not a silver bullet. Its effectiveness will depend on the quality of the data it is fed and its integration into a strong, pre-existing safety culture.

Takeaways. Achieving a state of sustained excellence in process safety is one of the most significant challenges facing the HPI. The path forward does not lie in simply adding more rules or procedures to already-bloated manuals. It lies in building a deep and resilient organizational competence, founded on a culture of trust, learning and proactive vigilance.

The polymer factory case study tragically reminds industry of the pillars of process integrity: design, operations and maintenance can all crumble when the cultural foundation is weak. The recurrence of major accidents worldwide is a stark signal that a fundamental shift is required: from a mindset of compliance to a culture of commitment, from seeing safety as a cost to understanding it as a core value and from focusing on individual errors to addressing systemic vulnerabilities.

This requires a new kind of leadership, one that is perpetually uneasy, visibly present and uncompromising in its prioritization of safety. It requires a systematic and relentless focus on building the 10 pillars of competence, from training and psychological safety to continuous learning and proactive metrics. It also requires an honest confrontation with the industry gaps and human paradoxes that hold us back.

Ultimately, building a robust process safety culture is about creating an environment where every person, from the CEO/CMD to the contract worker, has the knowledge, skills and empowerment to make the safe decision every time. It is a continuous journey of improvement, one that demands dedication, investment and an unwavering belief that all incidents are preventable. For high-hazard industries, this is not just a strategic priority, it is a moral obligation.

Comments